|

|

|

|||||||

| Последние сообщения на форуме |

| Последние комментарии к фото |

| Новые записи в дневниках |

| Новые комментарии в дневниках |

| Новое в группах |

| Ссылки сообщества |

| Социальные группы |

| Поиск по форуму |

| Поиск по метке |

| Расширенный поиск |

| Найти все посты, за которые поблагодарили |

| К странице... |

|

#1

|

|

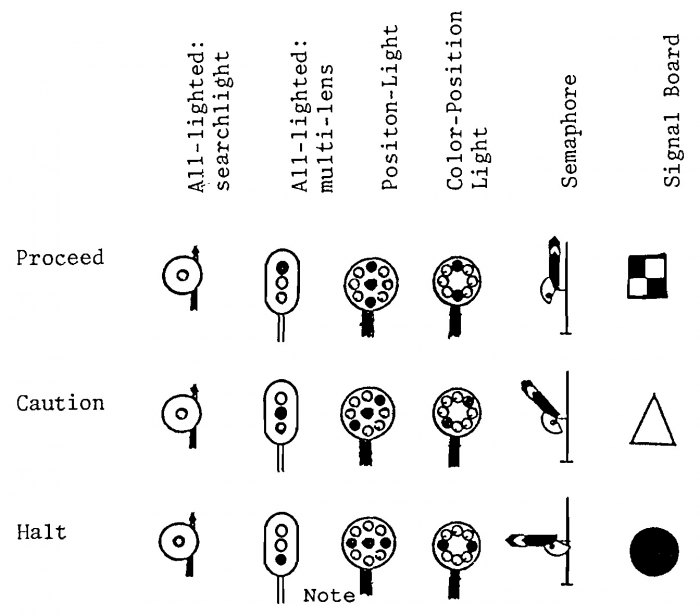

RAILWAY SIGNALLING: INTRODUCTION, HISTORY & METHODOLOGY 28a Introduction, Physical Properties and Semiotics of the Signal 28A1 Introduction The railway signal (and accompanying signs and non-sign markings) presents a diverse and variegated appearance. The railway signal is not only very complex but has a markedly reduced degree of commonality in comparison with marine, road and aeronautical transportation markings. This means that this monograph is not based on an already existing cohesiveness. Therefore it is necessary to include several basic perspectives in order to integrate the existing fragments of railways signals. One area of fragmentation is the strongly national, or at best regional, character of signal systems. Other transportation markings have achieved substantial convergence through global organizations or special conferences -with their resulting signal codes - while only limited agreements have taken place in railway signals. One can speak of "schools" of signals (for example the historic underpinnings of U.K., North America, the Communist bloc, and so forth). An overview of the "schools" may not create convergence but it can present the various approaches together and thereby provide a degree of convergence (Chapter 30A provides introductions to the "schools" of signals). Roland Barthes (1988,180-190) has written an eassy in which he notes that a human-made object is the focus of two connotations and of two coordinates (See also Chapter 1B2 of Part A, 2nd ed. in this Series). The coordinates are those of the symbolic and of classification. Those coordinates form a vital core of the study. In addition, there is the object in itself. For this study the object in its own right focusses on the dimension of physical properties. Chapter 28A2 will examine that dimension within the headings of signal mediums, signal configurations within those mediums, and the nature of message capabilities. Technology in itself is not a focus of this study though a measure of technology is inherent with any study of transportation markings. The symbolic (or semiotic) coordinate of the signal, examined in Chapter 28A3, places emphasis on the semiosis and signification dimensions of the sign and how they can relate to railway signals. Chapter 28A3 gives only brief treatment of the classification coordinate since all of Chapter 29 is devoted to signal taxonomy. Chapter 28B centers on a review of the history of signals. The history segment illustrates some areas of commonality and shared developments for signals. Methodology, Chapter 28C, has importance for this study because of the fragmention both in signals and in documentation; an integrated methodology can help to bridge the fragmentation in signal and sources. 28A2 The Physical Properties of the Signal The physical properties of the railway signal, sign and marking include the specific medium signals can adopt, the actual configuration of the signal, and the nature of the message that the signal is capable of producting and emitting. The technological mechanism is not examined in this study because of the communication and symbolic focus of the study. Specific mediums have reference to how the signal produces and emits a message. The basic mediums are the visual, electronic and acoustical. The visual signal continues to predominate despite some inroads by electronics. The visual medium contains all-lighted, partially-lighted, and unlighted variants. All-lighted mediums can take several forms. These include color-lighted, position-lighted, color-position lighted, graphic, geometric, and alphanumeric (which can be alpha and/or numeric) signal forms. There are differences between graphic, geometric and alphanumeric signals though precise distinctions are difficult to articulate. This matter is further discussed in Chapter 31. Partially-lighted forms include the semaphore and what in the monograph is termed the signal-board. Other forms are found at points, switches and other locations. Partially-lighted forms usually have very different physical means for displaying day and night aspects. Unlighted mediums are largely found with signs and markings. Acoustical devices are not very common and are usually associated with cab signals and detonators. For many signals the medium does not have a single and unvarying appearance. For example, an all-lighted color signal can have one of several forms; one may have three lamps and another a half-dozen or more. One signal may have a square housing or backplate while another can be circular. These variations are termed configurations in this study. There are other possible differences in symbols: how the lamps are arranged, the presence or absence of marker lamps and other supplemental lights, the location of the signal. Chapter 29B, Variant Classification of the Signal, describes the types of differences found within the mediums accompanied by illustrations of shapes which are notably different. The amount of complexity within a given system consitutes a second area of differences. A system using only basic message indications requires a simple housing but a more complex system requires multiple signal heads and other features including marker lamps, light strips or flashing lights. Chapter 31B2 provides information on these more complex systems. There is a narrow and uncertain line between the physical properties of the signal and the semiotics of a signal. Signs closely integrate physical and symbol but for many signals it is possible to distinguish between the physical properties and semiotic dimensions. However, the nature of the message capability of a marking partakes both of the physical and of the symbolic. Yet the nature of the message that a signal can produce is tied more to the physical production of a message than the semiotic meaning. Therefore that topic is placed with signal meanings and configurations which do not deny the role of symbols. The nature of the message concept is first found in Volume I, Part Ai; it is reproduced here to provide a context for railway messages. The nature of the message that a railway or traffic signal can produce permits a variety of messages (proceed, caution, stop) while a marine aid to navigation, by contrast, can produce only one message and that message is single and unvarying. The basic construct of these message capability natures follows this pattern: 1. Multiple capability that permits Changing Message/Multiple Message (C3M); 2. Message capability that permits only Changing Message/Single Message (CMSM); 3. Message capability that includes an Unchanging Message but with Multiple Messages (U3M); 4. Message capability that is restricted to Unchanging Message and Single Message (UMSM). The fourth form (UMSM) includes the following sub-categories: I. Programmable Transportation Markings; II. Unitary Markings includes several variants: A. Single and unchanging message B. Intermediate which permits one of several predictable versions; C. Individual which includes markings for whom few, if any, predications can be made. C3M is the most important for railway signals since those signals emit a variety of message in an alternating order; for example, caution follows proceed and stop follows caution. CMSM, a rare category for any type of transportation marking, includes a few railway signals. For example, U.K. has installed signals at some secondary locations which operate only when that track is in use. The message is a single form but one that undergoes change. It is unlikely that there are any U3M forms among railway signals. This form refers mainly to road traffic beacons. A possible variant form for railways may be those signals at junctions of tracks where a proceed message for one track is joined by a halt message for the second track. UMSM-I, a mainstay of marine and aeronautical aids to navigation, has no role in railway systems. But the II sub-category includes railway transportation markings and especially signs. Variant A includes the system of electric traction signs common in Europe. Variant В includes speed signals since they encompass a limited number of differences. Variant С includes station identification signs because of the singular character of proper names, and also variant forms of graphic signals. 28A3 The Semiotics of the Railway Signals There is no need to review semiotics for this study, nor the semiosis - or sign process aspect - of semiotics. Semiotics can be briefly defined as the study of signs in whatever form. There are numerous works available on semiotics; there is also a brief survey in Volume I. However, two phases of semiosis need to be reviewed in this work: sign and signification. Sign (in a semiotics sense) can be viewed as the aspect that a marking (or other semiotic sign) displays. In some markings, such as unlighted signs, the semiotic sign and the physical dimension of the marking are virtually fused into one unit while in other markings the message and physical properties can be separated. Signification can be regarded as the meaning that a message conveys, for example, a fixed green light signifies or has the meaning of proceed. It may be noted that semiotic professionals may prefer physical sign, form or designator in place of sign, and they may further prefer message/meaning or designatum in place of signification (Givo'n 1990) . Within railway signals there are two terms that are important to a semiotic analyis: aspect and indication. It may be an overstatement to state without reservation that aspect = signification, yet there is a strong correlation of those semiotic and railway terms. And for the limited scope of this study it should suffice to regard aspect as equalling sign, and indication as equalling signification in meaning. It would be an overstatement to suggest that every rail system employs aspect and indication (and comparable terms) in an identical manner. Nevertheless, a high degree of correlation exists. This can be seen in a comparison of signal codes employing those terms or similar ones; regretably not all codes contain the key words. In most instance, those codes containing an illustrated chart of signals will head the chart with the appropriate terminology; for example, the "Codigo Fundamental de Sinais" of Portugal (CP 1981, 19) contains the headings of "Aspecto" and "Indicacao." Other codes without charts infrequently employ those terms. A representative sampling of codes from various systems indicate the already mentioned consensus of terminology. English-language systems and Romance-language systems use the same terms in almost all instances. Dutch and German codes - among others - employ equivalent terms (NS 1978, 36, DB 1981, 16). France, however, uses indications in place of aspect though the meaning is that of systems using the latter term (SNCF 1981). SNCF utilizes the word signification instead of indication and in translation the word holds to the meaning in English; that is the semiotic word as well. A few systems including those of South Africa, and New Zealand substitute the word meaning for indication and meaning can serve as a brief definition for semiotic signification (SAR 1964, 16; NZ 1989, 117). The Netherlands uses "Afbeelding" in place of the English aspect which can be translated as picture or representation, and the phrase "Omschrijving van het sein beld" can be translated as the definit ion of the sign image (NS 1978 ). The Germanic form (in this case for SBB) employs "Signalbild am" or signal picture or representation, and "Bedeutang" or meaning or significance (SBB Signale). The terms in translation when coupled with the illustrations in the codes suggest a substantial degrees of correlation with systems using aspect and indication. Within the topic of signification, two additional perspectives can be included: the precise role the signification may perform, and the type of symbol the signification is expressed. The roles in which signification can be expressed (in terms borrowed from traffic control devices), are whether a marking fulfills a regulatory, a warning or an information role. For many railway signs the role is one of information, though regulatory functions and some warning roles may be present with some signs. For railway signals the primary purpose is often a regulatory one (though a warning role is frequently subsumed within regulatory); in other words, the regulatory is primary and only when a train crew fails to heed it does a warning function become important. The second perspective centers on the form of the symbol by which the signal's signification is emitted: whether speed categories, or speed values (see Mashour 1974, 34). Speed categories attach word symbols to the signal message; for example, a yellow aspect in North America has the meaning of "Proceed preparing to stop at the next signal". Trains exceeding medium speed must at once reduce to that speed" (AAR 1956, BOTC 1961). Medium speed for the Association of American Railroads (AAR) is 40 mph though an individual railroad may substitute a lower speed. The medium speed is 35 mph in Canada. There is a lack of agreement on what yellow indicates and what medium speed indicates. There is a need on the part of the train crew to mentally shift gears from color to word to number and then to adjust when the meaning changes. This issue also pertains to the arbitrariness/naturalness of sign meanings. Word descriptions which need to be translated into a numerical code (and one that can vary) are more arbitrary than signs that immediately portray the numerical speed value that the train is to follow. What this compiler refers to as the intrinsic or extrinsic meaning of messages (and at least partially touches on the issue of stability of meaning) is considered in Chapter 30B. Speed values refer directly to numerical values: a green fixed light refers to 90 km/h and a green over yellow indication denotes 40 km/h and without words such as medium, limited or restricted. It should be noted that a numerical symbol for a color may differ from system to system. There is no complete and standard nomenclature of color and number. URO is the chief example of a complex system employing only number symbols (URO 1962). While Canada and the U.S. are examples of a complex system based on word symbols accompanied by numbers (AAR 1956, BOTC 1961). Other systems use a much smaller range of signification and accompanying symbols whether speed categories or speed values. Chapters 28A2 and 28A3 are separate yet closely interrelated topics. The physical and the semiotic parts of signals ought to manifest some relationship in this chapter as well as separateness. This can be easily done by a series of illustrations of the signals in their physical shape with the basic messages representing semiotics. This also provides an opportunity to illustrate how different forms of signals can convey the same messages. The illustrations and messages include all-lighted (search-light and multi-lens, position-light, color-position light), and partially-lighted (semaphore, and signal board).  A projected unit of Part A (Design and the Transportation Markings, Ch. 6) will focus on transportation markings as an aspect and manifestation of design for this Series. However, brief comments on railway signals and design will be included in this note. The railway signal in many of its forms may appear very dated; a prime example of low-technology, more than a little quaint, and a frequent reminder of the Victorian and Edwardian eras and all that they may conjure up. Microprocessors and electronic train control add a patina of modernity to the great assemblage of visual signals but no more than that. Despite some modernizing inroads, many signals - at least in design - are little changed from nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; many other signals follow designs that are derivatives of the early signals. Despite dire predictions of the imminent demise of visual signals of whatever form, not infrequently the trains have vanished well before the signals have. In many instances, signals do not - upon close inspection - manifest an outdated appearance. Often they are marked by a stark simplicity: form closely follows function. They are notable examples of minimalism accentuating clean and unencumbered lines. Simplicity, function- inspired form and minimalism contradicts neo-traditionalst design especially in architecture of both the 1880s and 1990s. Yet many other forms of design also exhibit those characteristics found in signal design including transportation equipment, communications technology, running/biking/aerobics gear with their "second skin" look. Much of contemporary design has not swerved from simplicity and functionalism and may have focussed more strongly on those characteristics. If one separates the signal in itself from railway transportation that can appear archaic (at least in the U.S.) and no longer a trend-setter, then it may be possible to view the signal as an object that, if not timeless, is at least an object that follows a timeless path of simple geometric shapes, economical usage of materials and excludes superficial and useless decoration; it is less often influenced by what is momentary (this does not eliminate the need to study the meaning of signs and changes in their meaning). The signal parallels not only contemporary design but that of past eras as well. The signal is then part of the present and not a musty anachronism of the past. 28В Aspects of the History of Railway Signals 28B1 The Formative Period, 1830-1920 The history of signals can prove to be elusive. Only limited independent treatments exists, and no global treatment has been attempted or so it would appear (Brian Hollingsworth, in his Hie Pleasures of Railways, notes that even for the U.K. there is a large gap in railway literature for the topic of signals and this is true of few other railway topics; Hollingsworth 1983, 43). While the story of the railway signal exists it is frequently embeded in the larger history of railway development. Much quarrying is required to unearth even fragments of that history. The effort can prove to be worthwhile since even scattered shards can illumine contemporary patterns. And the past and present are often fused together in railways. The following few pages, while only cursory, may suggest some of the unfolding of signal history. Chapter 28B1 may give undue coverage to U.K. and U.S.* However, many developments and their applications took place in those nations. Developments that came about in other locales in earlier decades were often based on U.K. and U.S. foundations. Chapter 28B2 will give greater attention to other systems. The formative period of 1830 to about 1920 can be divided into three unequal parts: early developments, 1830s-1860s; further advances, 1870s-1890s; early modern phase, 1900-1910s. Of course these are somewhat arbitrary divisions and they can be debated both as periods of time and of content. A common thread running through the phases will be the persistence of signals and colors and meanings once they have been established. Some systems continue to maintain signals and indications established in the nineteenth century; if not by the founding system then by some other system(s); a good example are signals with a blind-edge which fell out of use in the U.K. but are in use in other systems to the present (Ellis, 35). Early U.K. signals were often boards or flags for day use and lamps at night. The dominant color scheme was white for clear (which continued in U.K. and the continent of Europe until the later nineteenth century, later in the U.S.); green for caution and red for danger. The cross-bar signal used the "edge-on" (signal parallel to tracks for proceed) approach for a clear signal as do many signal boards (Allen, 140). O.S. Nock (1962, 89) notes the on-edge approach in early twentieth century France yet U.K. is the probable source of that signal even if it died out in the U.K. A ball signal was employed in U.K. for a limited time and more extensively and for a longer period of time in the U.S. (Allen, 140). In one version of this signal a raised white ball designated that the train had left the station while a black ball indicated a delay or other problem (AAR, HDRS, 21). White was the line clear color in that time. Black is not a signal color though it forms part of the color indications for contemporary French cab signals; it is most unlikely that any historical connection exists (Ch 31B4). U.S. practice moved away from balls to large red discs which employed the edge-on indications for line clear. U.K. and U.S. left behind non-semaphore signals but other systems adopted and kept the old pattern. Semaphores can be traced to ancient Greece though it was in eighteenth century France that Chappe developed the semaphore as a long-distance system of communications (Nock, HT, 329). It was in the U.K. that they first became a railway signal system (Nock, HT, 329). The earliest semaphores were three-position lower-quadrant forms (in contrast to later U.K.-U.S. practice which has two-position LQ (however,some three-positions LQ semaphores were made in the U.S.; SSS 1975, 15), and if more than two-position, then two arms are in use (there are some three-arm LQ semaphores with extended capabilities; for example, Southern Pacific of San Francisco; Southern Pacific, 130-132, 137). The early version required the clear indication to be located in a slot in the signal post (yet another type of passive or invisible messages for the clear indication (Blythe 1951, 52). This form of signal - which indicated clear for the normal position not danger - did not always function when a heavy snow-fall weighed down the control cables. This meant that the clear indication position could not change to the danger indication. A serious accident caused by this malfunction lead to the demise of the slotted signal (Blythe 1951, 53-54). The first twenty years or so of railway signals was a fertile time of development. The next two decades were seemingly much less so. Signal types were sometimes added, sometimes dropped, but notable developments - other than expansion of existing forms - were limited. The 1870s-1890s by contrast was a time of great change. Germany adopted a signal code in 1875 (Signal-ordnung). While a brief document it presents a complete system of signals. Other forms of signals in the present code (DB 1981) date back to the nineteenth century. France did not adopt a code until 1885 (Rapport). Again, a variety of increasingly marginal signals in present practice (SNCF 1981) stem from that document. The diamond-shaped and checked signal boards were replaced by square checks that are still in use (Allen, 146-147, SNCF 1961 and 1985). White became a liability as a clear color, and gradually faded out in favor of green. Red remained as the halt and danger color. The commonly-employed two-position signals of UK did not require yellow or other caution indication. UK resorted to the tumble-arm signal which caused the signal to return to danger; breakage of the signal's connections would also cause the signal to return to that position (Shackleton, 232). German semaphores were of the upper quadrant form and two positions; these signals are of a different design that those of UK. UK employed fewer aspects but provided bracket signals at junctions while Germany increased the number of aspects and thereby addressed signal needs at junctions (Allen, 144). French semaphores, were only one element in the panoply of French signals, employed LQ signals. "Blind- edge" signals in French practice and some other systems are vertical units on a pivot while Germanic practice (and also that of the Netherlands) employed a signal board that was hinged in the middle so when clear the signal would lay flat instead of presenting the narrow edge to the track (DB 1981, NS 1978). British practice extended to systems outside of Europe including the rapidly expanding system in India (IPR 1896) . The earlier part of the twentieth century is marked by further developments in the semaphore (both the high point, and the beginning of its decline occured almost simultaneously), by notable advances in color science and glass manufacture, and a near explosion of forms of all-lighted signals both color and position. The semaphore began as a simple mechanism in the nineteenth century and developed into a sophisticated and automated machine. The products of the industrial revolution, electricity production and transmissions, motors, even gas-powered devices, brought the semaphore to its zenith. But the technical improvements were unable to change its basic character: one means of message production were needed during the day, and a separate one during the night. As with refinements in horse-drawn transport or steam locomotives, the advances were really little more than sophisticated tinkering. The last stage - at least in the American experience - was possibly reached in 1911 and in 1912 with the introduction of electric upper-quadrant semphores with the mechanism of operation occupying the top of the mast rather than the bottom (AAR, HDRS, 69; the 1981 Brigano and McCullough study, though commissioned by a single railway signal works, is also an important source with many interesting points). Color-light signals existed but only as a rarity in the nineteenth century; UK, for example, was the site of such signals underground in London in 1906 (Ellis, 84), but most applications were above ground and color-light signals were too weak to be seen very far in the daytime; though it was determined that all-lighted signals were feasible (AAR, HDRS, 69). It would take the same technological impetus that was futilely applied to the semaphore to bring about a revolution in all-lighted signals. Lamps, lenses, reflectors, high quality and consistent grades of glass were all required to produce a mechanism that could be seen a satisfactory distance in the daylight hours. Possibly the earliest daylight all-lighted signals were produced in the U.S. in 1904 though it required an incremental development to finally produce long-range signals (in about 1914) (AAR, HDRS, 70; also Brigano 1981, 139). A new form of all-lighted signal, the position-light, began service in 1915 (Pennsylvania Railroad). This signal employed rows of lights corresponding to the position of semaphore arms (Armstrong 1957, 12). The lights were of one color, yellow (which is sometimes referred to as amber since railway signal yellow is less saturated, Kopp 1987) . At the end of the 1900-1920 period a searchlight signal was invented (Brigano 1981, 140 and other sources). This contained a more complex mechanism in that three lenses were installed and programmed to slip into position as required instead of three, or more, independent mechanisms within one housing (Armstrong 1957, 12). This was to become a significant signal for a variety of systems though little known on the continent of Europe. Finally, and slightly more into the modern era, was the color-position signal. This too was a U.S. development. It combined rows of lights (corresponding to the semaphore positions as with the position-light signal) but in color. This signal has met with only limited interest and is largely confined to the Baltimore and Ohio, Chicago Terminal, and Gulf, Mobile, and Ohio, and Chicago-Springfield-St.Louis lines (AAR, HDRS 139; McKnight 1990). What are termed position-light signals in many systems (and for usually non-mainline purposes) are often color and position light signals though perhaps of an independent development. A second major development in the early twentieth century was centered on color and meanings. Already in the nineteenth century U.K., as well as other European systems, were employing red for halt/danger and green for proceed/line clear (see previous segment). The very large U.S. railway industry was slow to make the change from white to green for proceed and to add yellow. However, the change, though slow, was firmly based on scientific and technological research and the resulting colors, meanings, glass standards and consistency, were to have any impact throughout the century (ARSPAP-11, TISRPS; also Brigano). And the conversion to green was made quickly after the decision was made (McKnight 1990) . Much of the work on the development of color was undertaken in the years 1904-1906. This included setting of limits for colors and deciding the contents as well. As a result the (U.S.) Railway Signal Association adopted green for proceed and yellow for caution in 1906. During 1905 the Corning Glass Works and RSA worked out specifications for colors and these took the place of individual road standards. 1910 marked the general usage of red/yellow/ green and the fading out of white as a principal color (of course white is found with dwarf position-light signals, and lunar white - a blue-white - was added some years later). The color specifications not only provided consistency and reliability but the scientific study created a yellow that could not be confused with any other color hue, and thereby created a cautionary color that permitted green to become the proceed color. The U.S. was more inclined toward three-positions than many other systems; at least in the developmental stage. Early in the twentieth century (EB 1910 Vol. 22, 823-824) noted that the U.S. had just short of 40% of the world's trackage. Six additional systems had from 3-6% of the trackage, and four other systems had 1-2.5% each. These 13 railway systems had 85% of all of the operational tracks. U.K./Ireland (#7), British India (#4), Australia (#9) and South Africa (#13) constituted a second very large inter-related signal pattern. Other British dependencies, Canada, and some major South American railways were also heavily influenced by U.K. Germany (#3) also had influence well beyond its boundaries as can be seen even today in many signal indicator types. An examination of statistics for Europe (1840-1870) underlines the permier role of U.K. during much of the first development stage. In 1840 U.K. had nearly three times the trackage of Germany and France combined; by 1850 U.K. maintained its lead though more narrowly. Even with major German and French expansion, U.K. maintained its first place position though only by a thin margin in 1870. Colors, blind-edge signals, semaphores were all areas where U.K. created and where others frequently adopted or at most adapted (EHS, 581-583). 28B2 Further Developments, 1920-1980 1920-1980 is a time of great changes for railway signals and signalling." It was a time, especially after world War II, of major switching from semaphores to color-light signals. New forms and variations of color-light signals were developed especially in Europe. Cab signals and many electronic mechanisms also came into service. Yet much of the ground work for these changes already had taken place: much of the glass technology, color standards, basic forms of all-lighted signals were in position for broad use by about 1920. One important area for signals in this period would be attempts at international cooperation; regional and more than regional cooperation would fashion new signal codes with new ideas. Belgium, because of widespread destruction in World War I, created a new system of signals that incorporated new ideas (Nock 1962, 79-83, TISRP). But this system remained tied to the prevalent semaphore dominance of that era in contrast to conditions after the next war. A notable event with far-reaching implications was the work toward a new concept of signals in UK. Even though much of U.K. modernization did not take place until the 1950s, the ground work came three decades earlier. High points of the work, involving IRSE and the Board of Trade included the advocacy of three-position signalling over the main form of two-position. Yet the recommendation was for color-light rather than three-position semaphores. And a fourth aspect, a double yellow, was also called for. This new signal was needed to cope with special situations that a single cautionary indication could not respond to. The notion of a double yellow was to be emulated by many systems in coming decades though in some instances a green over yellow was in use rather than two yellows (G/Y was under consideration in U.K. at one point). Semaphores in their various forms and signal boards may have dominated Europe in the inter-war period but some systems were moving toward general usage of color and all-lighted signals. The U.S. was the outstanding force in this direction. But Australia and New Zealand provide examples of movement toward all-lighted signals as well. New Zealand exemplifies the pinnacle and rapid decline of the semaphore (as was seen earlier in the U.S.). In 1922 New Zealand introduced the three-position UQ automatic semaphore but in less than two years all-lighted color signals were also introduced (NZR, "Century"). "Fine-tuning" of the old collided with a much more advanced signal. But in these systems as in others, semaphores were still growing in at least some areas for several more decades even though a general decline was increasingly evident. Even in present times the old continues to exist though it may be largely confined to less important tracks and slower train movements. Signals, from somersault semaphores to the most advanced forms of semaphores, continue to be found all over the world. Signal boards are still found in Europe, portions of Asia and Africa. World War II wrecked havoc upon all aspects of life both individual and social. Railways and their signals fell as well. The largely intact system of semaphores and boards declined sharply in a few years. Many systems created new ideas in signal practice. Some correlation can be observed among signals though notable variations exist. For example, the French have introduced a complex system based on almost curvaceous signals while the Germans have a less-complex system housed in sharp and angular signals. The Italians and Dutch make use of substantial numbers of search-light signals. Unfortunately guidelines for signal indications took place after much of the changeover in signals had occurred. The sense of an integrating Europe came too late to prevent a variegated signal apparatus. As signals produced in various nations are transplated to non-European nations the curved signals and the angular signals crop up in far-removed locales; for example, RAN followed SNCF practice, and siemens influenced SAR. U.K., U.S. and Japanese upright rectangles and and searchlight signals (through Westinghouse companies, GRS, USS, Nippon and others) have also moved beyond the original borders so an overlapping mosaic of various shaped signals results. Agreed-upon forms are often conservative and long-lasting as can be seen in century old semaphores. Three events, too new to be regarded as historical - unless one perhaps subscribes to "instant history" - are the signal codes or guidelines of IUR, URO and UAR. IUR, during the 1950s and 1960s worked to create a system for its members especially in Europe. But existing signals were too entrenched for success of the new ideas (Though work on signals for high-speed trains was more possible). But IUR did produce guidelines based on common practices and these may shape future signal developments (see Chapter 30A). URO, the Communist Bloc system produced a full system in the early 1960s and one that is operational and highly integrated. It is a system that is complex upon first examination but has a simple and highly rational message system upon more study. Variants of this are found in Poland, DDR and other member-states. The system also includes some older signals especially those associated with Germanic formsignals. UAR, in the past ten years has also created a system of signals. This code incorporates British and French approaches as well as a contemporary color-light system. UAR eliminated the long-enduring blind-edge for signal board clear messages though at least RAN (in the French tradition) holds to the blind-edge rather than to the UAR form (see codes of IUR, URO, UAR, PKP, DR, etc for references to this segment). Even though great diversity continues to be found among signals there are some points of commonality even if not full-scale convergence. The forms of signals and color messages bear some similarity though a convergence akin to road, marine or aero markings will probably never take place. |

|

|

||||

| Тема | Автор | Раздел | Ответов | Последнее сообщение |

| US&S Railway Signaling Equipment | art29 | Общие вопросы железных дорог | 0 | 02.07.2011 11:24 |

| HollySys' Railway Automation | Admin | Wiki | 0 | 18.02.2011 20:59 |

| ALSTOM Signaling Inc. history | Admin | Wiki-Railway | 0 | 18.02.2011 20:28 |

| RAILWAYS AND WAR before 1918. LIGHT RAILWAY LOADS (60-cm. gauge) | Admin | Wiki | 0 | 18.02.2011 16:58 |

| RAILWAYS AND WAR before 1918. Introduction | Admin | Wiki | 0 | 18.02.2011 15:31 |

| Здесь присутствуют: 1 (пользователей: 0 , гостей: 1) | |

|

|